For four days now I have been in Budapest, a witness to a drama that I would have considered impossible in an EU capital not long ago. Budapest-Keleti: this train station has become a symbol of EU member states’ inability to develop a solidary refugee policy and finally to abandon the failed Dublin Regulation, which requires refugees to register and submit their asylum applications in the country in which they enter the EU. This regulation is not solidary, because it overwhelms countries that have external EU borders in the context of the current influx of refugees. The Dublin Regulation is not adequate to meet the present challenges and has become merely an instrument of mutual recrimination and shirking of responsibility, the consequences of which we are currently experiencing in Hungary as well.

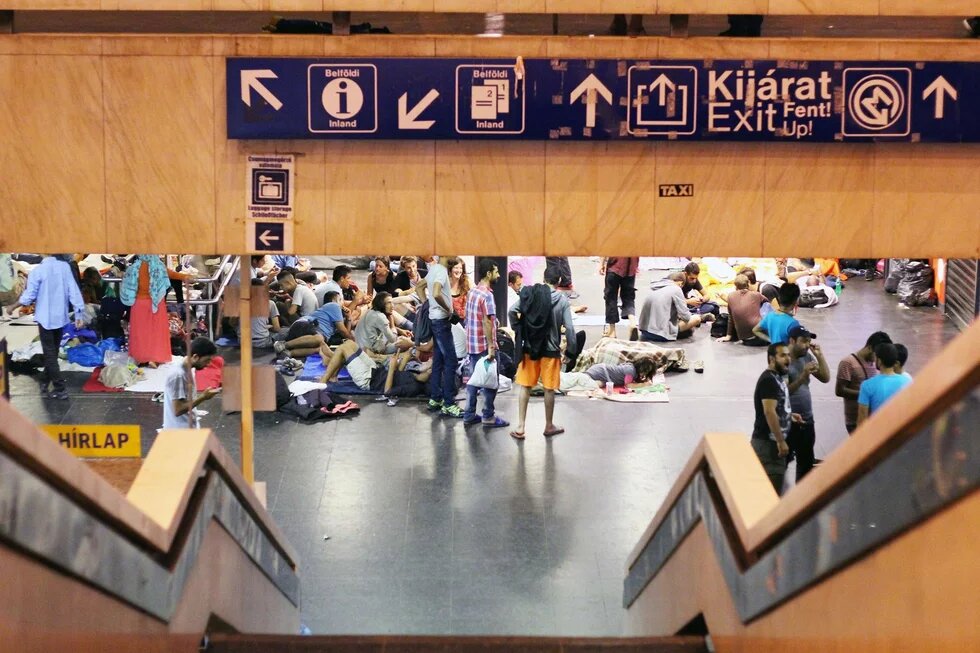

I need not describe the images; we have all seen the television footage. I am on the scene, moving through the inhuman chaos for which the Hungarian government and with it the entire EU are responsible. There is no explanation and no excuse for this scandal. Thousands of refugees have been held for days on forecourts and in undercrossings around Keleti and Nyugati stations. On Friday, some 2,000 people began the journey to the Austrian border – on foot: women, children, men, along the motorway and on railway tracks, exhausted, hungry and desperate. And this in Hungary – in the EU.

On the same day, the police were busy containing a group of unruly hooligans who, on the occasion of a European Championship qualifying match between Hungary and Romania, had descended into the capital with black shirts bearing the word “Magyarország” (“Hungary”) and other symbols of the right-wing extremist party Jobbik, yelling a full-throated “Hungária” at regular intervals and attacking refugees.

The images of the refugees, who had begun the journey out of Hungary peacefully and on foot, were evidently too much for Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. During Friday night, the Hungarian government organised buses to dispatch the “German problem” out of the country as fast as possible, and on Saturday morning the Austrian and German governments agreed to grant passage to the refugees. This does not resolve the situation, however.

Refugees are not welcome

Refugees are not welcome in the member states that acceded to the EU in 2004 – this is what most of these countries’ heads of state and government have repeatedly and often tastelessly indicated, to a greater or lesser degree. With striking frequency and in mutual agreement, they shake hands here over matters of refugee policy – despite the fact that the numbers of approved asylum applications in recent years are extremely low in all member states. There is no trace of a sense of responsibility, only panic and conviction at the prospect of losing favour with the voters if one were to try to push back against the widespread resentment of refugees. Instead, they are pouring oil onto the fire: A few months ago, Orbán flooded the country with signs in Hungarian bearing slogans such as “If you come to Hungary, you may not take any jobs away from Hungarians; you must follow our laws and respect our culture”. Czech President Miloš Zeman informed refugees through the media that no one had invited them to the Czech Republic. Czech Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka presented the failure of an EU Commission proposal to implement binding quotas for member states to take in refugees as a success of the Czech government, and Slovakia’s Interior Ministry let it be known that the country would prefer not to admit any Muslims, as they surely would not feel comfortable there.

Last Friday, the Visegrád Group (Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and the Czech Republic) reaffirmed its closed stance and its “no” to admission quotas for refugees. Prime Ministers Ewa Kopacz, Robert Fico, Viktor Orbán and Bohuslav Sobotka – conservative, left-wing populist, right-wing populist and social democratic, respectively – this makes no difference on the issue of refugee policy; they all understand each other. This consensus and the showcased unity of the Central European countries stand squarely in the way of a solidary refugee policy. And this does not augur well for the next EU summit.

English translation: Evan Mellander