Special anniversaries are always a good occasion on which to ask the principle questions featured in the title of Gauguin´s famous painting: “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” Let´s do that for the Visegrad Four group now that it is celebrating its 30th anniversary.

On February 15, 1991, the presidents of three Central European countries – Václav Havel, Lech Walesa, and Árpád Göncz – signed a declaration on their regional political cooperation. The location of this act could not have been more symbolic – it was performed at Visegrad Castle where, in 1335, Hungarian King Charles Robert of Anjou met King Casimir III of Poland and John, King of Bohemia and Count of Luxembourg to discuss neighborly cooperation and peace and in Central Europe. The meandering of the Danube River through this area seems to resemble the development of the V3 into the V4, over the last three decades: periods of enthusiasm have alternated with times of doubt about the raison d´être of this grouping.

However, unlike other regional initiatives and cooperation pacts, Visegrad is still alive. That fact has resonated quite often in the interviews, politicians’ statements, and reviews published around this anniversary. Staying alive - but is this unconvinced note enough? Though the group may not have been able to live up to all the initial expectations, a lot has been achieved by it.

Cost/Benefit Analyses

The point of Visegrad cooperation is based mostly on the common destiny of its four nations, which were parts of different states in the past. Today they live side by side as democratic, sovereign states whose security is guaranteed by the Euro-Atlantic community. Without any doubt, this has contributed to enhanced stability and deepened cooperation among these Central European states in areas such as education, culture, science, the environment, the fight against organized crime, regional development, civil society development, transport, etc. Above all, however, the fundamental mission of the initial Visegrad idea has indeed been accomplished. All four countries joined the EU and NATO, even though for Slovakia that seemed like “mission impossible” in 1998, but the regional alliance became part of their strategy for reducing their integration deficits. “The road to Brussels goes through Visegrad” was the mantra of the years when Slovakia was catching up its neighbors.

It is not a purely poetic cliché to state that Central European countries share common interests. Discussing the historical perspective, Daniel Hegedűs, non-resident fellow for Central Europe at GMF (German Marshall Fund), recently emphasized that after 1989, these countries, for the first time in their history, are able to define their own destiny without pressure from outside. A “kidnapped” Central Europe – which was the thesis of Milan Kundera’s seminal 1984 essay “The Tragedy of Central Europe” – is now the past. These countries belong to Europe, not just geographically, but politically as well.

Nevertheless, what was their vision after the 2004 EU accession? The sense and purpose of Visegrad was challenged, especially when there were expectations that the countries would act in concert at different international forums above and beyond the EU. Was that realistic, though? Similarly, already in 2002 Pavol Lukáč, an excellent Slovak historian and political scientist, wrote: “I am fully aware that Visegrad is far from being a compact political entity adopting the same strategic plans and trying to find political instruments for their implementation. However, if there is a will, they can approach this goal, which is the only way the individual countries can better their marginal position as small countries not just on the geographic periphery of Europe, but also on the actual periphery of political influence.”

The V4 countries have failed to fulfill this ambition, and the coordinated actions that were the great topic of a possible joint agenda - on the Balkans, for instance - did not take place.

EU vs V4

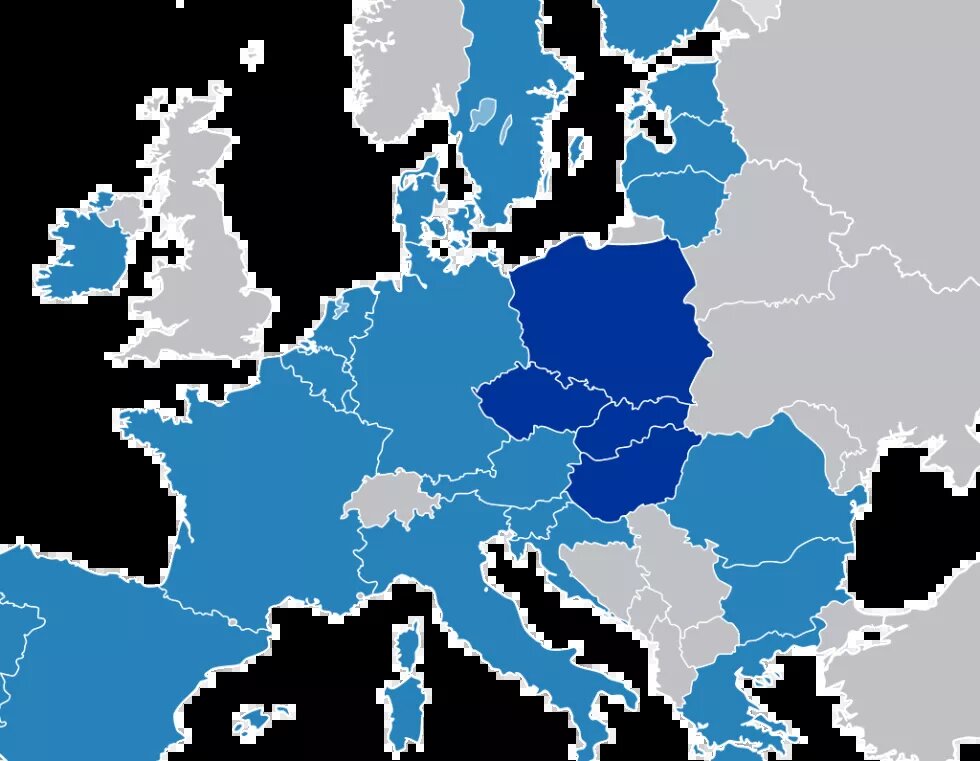

During the first years after joining the EU, the V4 countries were relatively “silent” members. There were tensions over some issues, like the later ratification of the Lisbon Treaty in Poland and the Czech Republic, but with the exception of Poland, the smaller countries were more “policy takers” than “policy setters”. The real conflict came in 2015, when the EU approved quotas for refugee relocation after the dissenting votes of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia were overruled. The Polish government initially approved the relocation scheme, but was then heavily criticized by the opposition, and after the victory of PiS in the general election in October 2015, anti-migration policy became a reality there. With that, the V4 countries were unified on rejecting migrants, declining solidarity and not assuming responsibility. Their positions on this issue were driven by anti-migration, xenophobic discourse domestically. Furthermore, such appeals were not just coming from radical right extremists, but also from governing, mainstream politicians as well. Consequently, there was a spill-over effect – the rise of a Eurosceptical mood among the population.

In parallel with the migration crises, the issue of democratic backsliding and the breaking of the rule of law in Hungary and Poland started to be THE issue, with negative consequences for the image and reputation of the entire V4. The narrative of the V4 as the V2+2 started to emerge more and more frequently.

The democratic deficits of the Polish and Hungarian governments have attracted a lot of attention and harm the image of the whole region. In recent years (Fidesz has been in power since 2010) Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has used the “salami method” to restrict the independence of the media, the judiciary, and NGOs, pushed through electoral reform favoring his party, fought against the Central European University, and taken a lot of other steps to hollow out Hungary’s democracy. In 2019, Freedom House downgraded its assessment of Hungary to “partly free” due to “sustained attacks on the country’s democratic institutions”. However, pressure from the EU did not stop this trend. Orbán famously described the game he plays with the EU as a “peacock dance” – three steps forward, one step back, and spread your colourful feathers,” wrote Timothy Garton Ash in The Guardian. That is a very concise description of Orbán’s strategy.

There were moments when one had the feeling it could not go on – for example, Hungary’s billboard war against Jean-Claude Juncker prior to the 2019 EP elections, connecting Juncker to George Soros, Orbán´s symbol of all that is evil. However, Orbán knows that the EPP needs Fidesz's representatives, so he took one step back and then three forward by blocking approval of the EU's budget over a clause that ties funding to adherence with the rule of law in the bloc. Hungary did this together with Poland. Nevertheless, at the end of the day, a compromise was found.

As for Poland, the European Union has repeatedly expressed its concerns about the erosion of democratic norms there. Especially LGBT people and the independent media are under enormous pressure. Recently, massive protests came about as a reaction when the Constitutional Court ruled that abortions must be banned irrespective of the reason they are sought, even in the case of fetal defects. The movement against that ruling grew into the largest anti-government mass movement in Poland since communism fell more than 30 years ago. Hungary and Poland were once the best pupils of transformation and integration in the1990s. Their recent developments have raised substantive questions about the sustainability of democracy.

Where are we going?

In spite of all these controversies, nobody dares say there is no future for Visegrad. Slovak Minister of Foreign Affairs Ivan Korčok, a genuine, firm pro-westerner, has pointed out that the V4 should definitely be neither a unified block within the EU, nor a kind of protection against the EU, but rather a stable component of the EU. Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš does not want to see the V4 as a political bloc either. According to him, the V4 is not a political bloc but “an economic bloc of 65 million of our citizens, for whose interests we are fighting. And, of course, we are also fighting for Europe's interests.” Today, many Slovak and Czech politicians are aware that when it comes to enforcing something in the EU, the V4 brand harms more than helps. However, most of them add in that same breath that there is still no reason to leave the V4 - rather, political cooperation should be limited or even stopped.

Finally, we cannot bypass today’s biggest challenge – pandemics. Recently it is the Czech Republic and Slovakia above all that are severely affected. The summit of prime ministers in Krakow on February 17 was hardly a “Happy Birthday” party. The debate was about vaccines, those that should be coming from the EU, but are restricted, as well the Russian Sputnik V. Hungary is – so far – the only EU member that has purchased and is using the Russian vaccine, and Slovak Prime Minister Igor Matovič is trying to follow this path, saying: "My opinion is very close to that of Viktor Orbán.” The protection of health and lives cannot be linked to geopolitics, though, the virus does not care about East or West. It is our duty to ensure a safe vaccine no matter where it comes from. Matovič is ready to negotiate with Moscow before Sputnik V is approved by EU regulators. Could this indicate a new Slovak-Hungarian axis within the V4?

We will see. If a period of more or less intensified cooperation lies ahead of us, then the V4 countries will continue to be the closest of neighbors bordering regional allies. The light is still green, so let´s keep going.