In Hungary, NGOs are now required to register as “civic organisations funded from abroad” if they receive financial support from a foreign source. The government is trying to delegitimise any organisation that criticises certain government policies, says Veronika Móra.

On 13 June, Hungary’s National Assembly passed the Law on the Transparency of Organisations Receiving Foreign Funds (with 130 yes votes out of 199). Under the law, NGOs are now required to register as “civic organisations funded from abroad” if they receive financial support from a foreign source in excess of EUR 24,000 per year. We spoke with Veronika Móra, director of the Hungarian Environmental Partnership Foundation (Ökotárs) about the consequences.

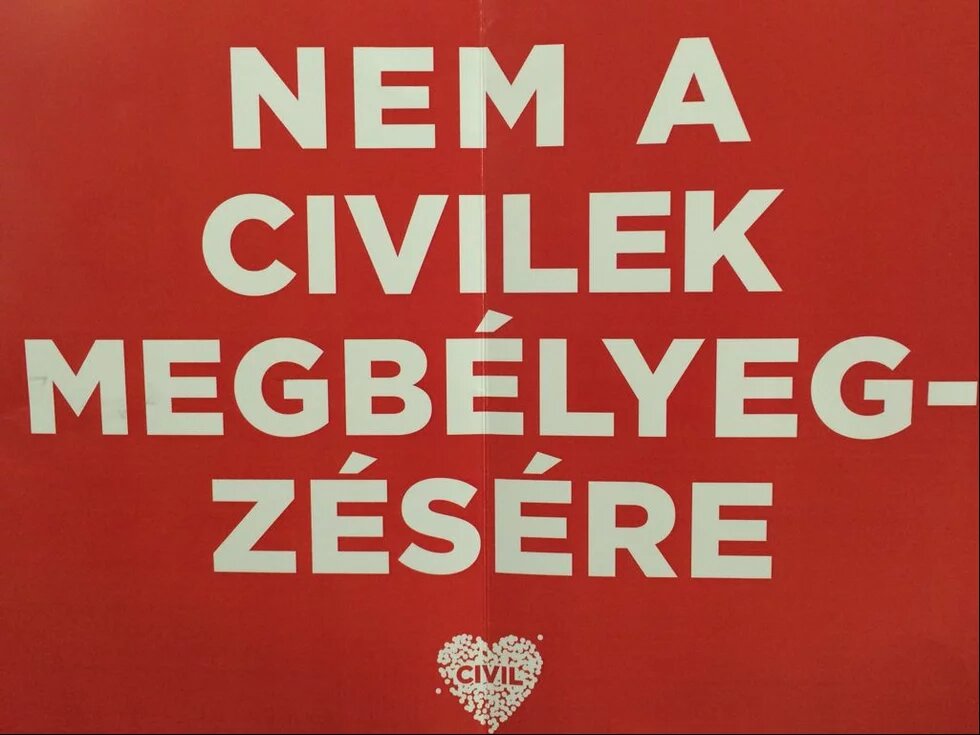

Ms Mora, together with almost 300 other civil society organisations united in the Civilizáció coalition of Hungarian NGOs, you published a joint protest letter in which you condemned the law as “unnecessary, stigmatising and harmful”. Why do you consider the label “foreign-funded” to be stigmatising?

Veronika Móra: Well, the law doesn’t stand by itself; it’s accompanied by an increasingly intensive campaign of government propaganda that has been underway for the last few years but has intensified since the beginning of this year. It clearly aims to discredit NGOs that use international funds by characterising them as organisations which do not serve Hungary’s national interest. It implies that these organisations are working on some foreign agenda serving foreign interests or organisations, especially in the context on migration but not only that. The government is trying to delegitimise any organisation that criticises certain government policies or speaks out publicly on behalf of various vulnerable groups, such as Romas, the disabled, and refugees.

Is the government’s aim to polarise NGOs in Hungary by dividing them into “good” ones and “bad” ones?

Yes, implicitly that’s part of the story. It’s quite clear that the Hungarian government views NGOs as organisations that should only be engaging in very traditional charitable activities. Those that go beyond charity and venture into advocacy are not welcome.

Did the new law divide the NGO community in Hungary or, to the contrary, has it brought you together, as your joint protest against the law might suggest?

It’s difficult to say. Just to give you a broader picture, there are some 55,000 – 60,000 registered NGOs in Hungary. However, about 80 percent of them will not be affected by the law because they simply work with budgets below the threshold. At the same time, the coalition of NGOs that has been forming since the beginning of the year managed to garner the support and signatures of more than 270 organisations for its joint statement. And of these 270, there are about 20-25 larger, nationwide organisations that now collaborate on a regular basis, organise joint actions, issue joint statements, etc. This core group is also broad-based in the sense that it includes human rights organisations, environmental organisations, organisations working in education – all sorts, which is quite unprecedented in Hungary. So in a way, these attacks have managed to bring NGOs together and enabled them to grow together and be in solidarity with one another. The joint statement was also signed by organisations that will not be affected by the law.

Is this solidarity due to the new transparency law or did this process begin already in 2014 at the start of Orbán’s campaign against NGOs?

Well, there was an earlier attempt to build coalition during 2014 when the NGO Programme of the European Economic Area/Norway was attacked, but that wasn’t really successful on the longer term. But since January 2017 we’ve been cooperating again, and so far this coalition seems to be more durable and stable than before. The text of the law was not yet known when the joint work started, but the government’s communication made it clear that they intended to pass some kind of legislation. The short-term goal of this coalition, which is called “Civilisation” or Civilizació in Hungarian, was to prevent this law from being passed, to protest against it, and to draw attention to its harmful effects. Of course now, since the law was passed despite the domestic and international outcry, the coalition will endeavour to collaborate in the longer term as well, and we’re currently in the process of devising a new strategy for that.

Do you feel that you have support from Hungarians who are not involved with NGOs?

Yes. According to public opinion polls that have been conducted recently, the majority of Hungarian society has a positive view of NGOs, and even of foreign-funded ones, but they have very little knowledge of what NGOs really are, what they actually do and why. Nevertheless, we managed to mobilise quite a large number of people during the protests this spring. For example, several thousand attended the demonstration on 12 April at Heroes’ Square. So yes, there is backing and support from some segments of society.

Did you also receive support from organisations in other European countries?

Yes, actually this is an ongoing process as well. For example, Civil Society Europe has already collected signatures from more than 500 NGOs throughout Europe for a declaration. These messages are an important source of moral support – they can’t repeal the law, but it’s important to keep public attention focused on the issue and not to let it be forgotten.

The law was passed despite a protest on the part of the EU. In early June, the Venice Commission – the Council of Europe’s expert advisory body for constitutional law – criticised the Hungarian government for its “virulent campaign” against foreign-funded NGOs, adding that the legislation imposes excessive obligations and disproportionate sanctions on NGOs. In response, the government made minor modifications but left the law’s main points in place, such as the labelling of organisations as “foreign-funded” and the threat to legally dissolve an NGO should it fail to register as such. What can and should the EU do now?

Well, one thing is that the law clearly violates the EU Treaty in the sense that it runs counter to the free flow of capital within the EU and is also discriminatory. We believe the Commission could and should initiate an infringement process[1] and take the issue to the European Court of Justice – not only to protect human rights and democracy, but simply because the law violates the EU Treaty.

Similarly to the “lex CEU”, which targets the Central European University?

I think these two laws went very much hand in hand, both within Hungary and in the EU. What we’ve seen at the protests and demonstrations this spring in Hungary is that people were motivated by both issues. One could see many banners with slogans such as “We need the CEU, we need NGOs”, so the two laws were regarded similarly. The same goes for the EU response, so for example a European Parliament resolution that was passed in mid-May calls on Hungary to repeal both the CEU law and the NGO law.

The director of the CEU, Michael Ignatieff, underscored in a recent interview with the Heinrich Böll Foundation that he was very happy about all the support CEU received, but that the most important thing for him was not the support from abroad, but the support of Hungarians….

I would agree with that. Especially in the case of NGOs, it’s quite clear that Hungarian NGOs are working for the benefit of Hungarian society. So it’s above all the Hungarian people who must defend themselves, their society and their democracy. International support and solidarity is very important but it’s first and foremost the Hungarian people who have to solve the problems of Hungarian society.

What concrete impacts does the law have for you and the daily work of Ökotárs?

From the day the law comes into force at the end of June, we will theoretically have 15 days to register as a foreign-funded organisation. If we fail to comply – and we don’t plan to do so – the public prosecutor will give us two warnings. Thereafter, if we still don’t comply, they will take the matter to a court, which will also issue a warning to the non-compliant NGO, and then the NGO can start to defend itself through the legal system. This will probably take a long time, although we don’t yet know how long. What does have an effect on our daily operations is the propaganda that goes along with the law, and the need to defend ourselves, to organise, to talk to the media, to publish statements and resolutions, et cetera, et cetera.

Do you think the legal process will end up at the EU level?

Well, I think it will be a combination of things; it’s very difficult to predict at this point. I’m certain there will be an EU response – or at least I hope so – because, as I mentioned, the law clearly violates the EU Treaty. At the same time, of course, Hungarians also have to show that they don’t agree with this law or with how the government is treating NGOs.

Do you expect more protests, big demonstrations?

Well, I don’t know. As I’ve said, it’s very difficult to make any predictions about anything in Hungary these days, because the situation is changing so rapidly. We’re going to have general elections next April, so from the autumn onwards we can expect very intensive political campaigning, and who knows what kind of issues will be raised. One thing is for sure, though: the NGOs that are affected by the law need to be prepared for a lengthy engagement and a long-term campaign of self-defence.

What about the law’s impacts on morale? Are these demoralising for your team at Ökotárs?

You know, at Ökotárs we lived through a similar drama in 2014 and 2015 when we were caught up in the controversy around the NGO Programme of the EEA/Norway grants. So we know how it feels to be attacked, and we know that solidarity among NGOs and among the people is a very strong force – on the psychological level as well.

From a Western European perspective, the Visegrad states – Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia – are seen as countries that neglect certain European values. On the other hand, the trend towards populist parties is strengthening in Western European countries as well. How do you view this discussion on European values?

It’s important to note, of course, that this populist tide seems to have turned recently – which is good news for us. But still, what we see is that the Hungarian case is contagious. For example, Poland has passed quite a few measures that are very similar to what was previously legislated in Hungary. International solidarity is very important, and we should build a coalition against these populist trends.

Do you think the Hungarian government will attack other NGOs?

Anything is possible. It’s clear that the government’s communication aims to portray foreign-funded NGOs as not being representative of Hungary and Hungarians, and as not serving the Hungarian national interest. I think there is still a lot of communication potential for them in this. Again, it’s very hard to foresee what their next step could be. For example, at the beginning of the year they were talking about a declaration of assets for NGO leaders, but then they dropped this idea and designed the foreign-funded NGO law instead. You never know what will happen next.

Thank you very much for this interview.

The interview was conducted by Silja Schultheis (23 June 2017).

[1] The European Commission launched an infringement procedure against Hungary for the new law on foreign-funded NGOs 13 July 2017.