The Hungarian government has embarked on a model shift that may offer the illusion of a solution in the short term, but in the long term, it could eat up our future. The economic philosophy of the Hungarian government has changed radically in recent years. Evidence of this change includes the relocation of dozens of battery factories and the Aliens Act passed last December.

Hungarian oranges and a Hungarian battery factory?

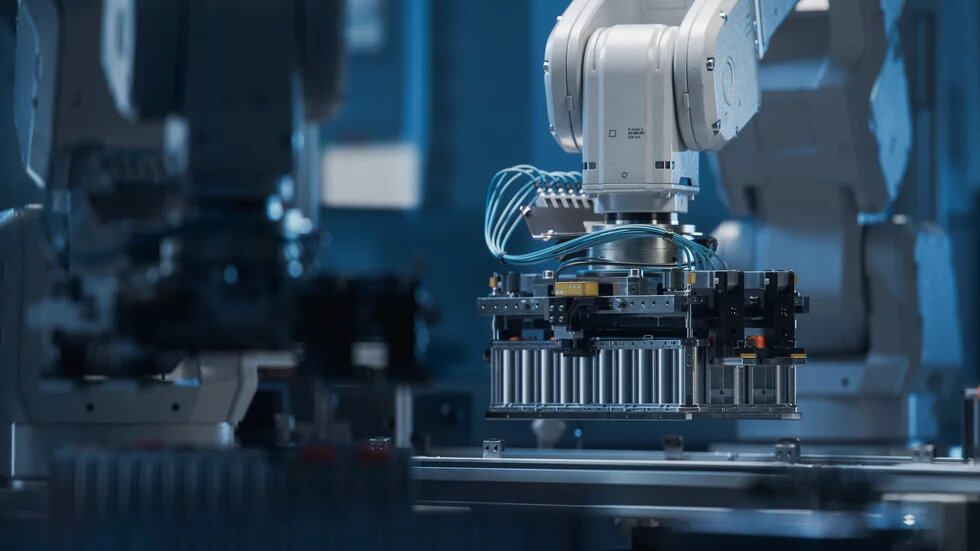

There are several possible explanations as to why the Hungarian government is setting up dozens of battery factories, despite the fact that workers next to the tapes can only be recruited from abroad. A fundamental reason might be to adapt to the transformation of the automotive industry, which is inevitable given Hungary's dependence – if we don't get caught up in remedying that dependence with even greater dependence.

One can speculate that if Hungary remains a critically important supplier to German car manufacturers in the future – even if it no longer supplies explosive engines, but rather only cheap Chinese batteries – this could also come in handy as a political trump card when Hungary's future in the EU is at stake. And Brussels or no Brussels, agricultural subsidies alone last year enriched companies linked to Lőrinc Mészáros to the tune of HUF 6.7 billion. (Lőrinc Mészáros is a friend of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a former schoolmate who, after Orbán came to power in 2010, began to make a spectacular fortune through his deals with the state, and went from being a simple gas fitter to Hungary's richest man.)

There is no doubt that the Hungarian government would like to preserve these benefits of EU membership without the (rule of law) obligations. In these games, Hungary's reliance on the German automotive industry, which is difficult to replace, is obviously a good thing, since Germany is perhaps the most influential state in the EU.

Another possible explanation is that Hungarian economic history is repeating itself; we are seeing an old motif being revived. What in the 1950s was cotton and Hungarian oranges (growing crops without adequate climatic conditions), in the 1980s was the Eocene programme (coal production without economically extractable coal), is now the relocation of battery factories (battery production without raw materials, sufficient water or available labour).

The common element in these stories is that the Hungarian political elite seem to have traditionally thought of the economy in terms of substituting the necessary preconditions for sheer political will.

A trapped economy

There may be truth in all of the above explanations, but the real reason is deeper, is structural, and is related to what economists call the “middle-income trap”. For a long time, it might have seemed that our country was not caught in this trap.

EU aid (and fiscal and monetary stimulus policies) have ensured growth above the EU average, which the government has tried to present to us as “catching up” with the advanced EU countries.

However, with EU aid drying up (and the loss of fiscal and monetary space), it has become clear that there are fundamental problems with the Hungarian economy.

What, in fact, is the middle-income trap? To put it simply, and to highlight the main point of our topic: for decades, Hungary's biggest competitive advantage has been cheap labour, it being the basis on which governments have lured foreign investors. However, as the economy develops, so does the cost of labour, so this type of competitive advantage is slowly starting to evaporate.

The system that has allowed Hungary to go from a low-income to a middle-income country (in short, economic growth based on cheap labour and foreign capital) is not suited to allow it to go from a middle-income to a high-income country.

From the government's point of view, the consequence of being caught in the income trap is not simply that the chances of catching up are destroyed (something hardly ever thought of too seriously). It is more than that. Nor can the peculiar Hungarian distributional model – a steady increase in the wealth of the upper middle class against a stagnating situation for the majority of the population and exponential growth in the wealth of the pro-government entrepreneur – be sustained any longer.

Economists' response to the problem of the middle-income trap is usually to “move up the value chains”, i.e. to move up from relatively low-skill assembly activities to more knowledge-intensive activities that are considered more valuable in the market.

Of course, this requires a lot of investment in human capital, education, support for innovation, etc.

So, what does the Hungarian government, which has so far only taken resources away from education, have to do with it, and what do the Hungarian battery factories, where only assembly is done, have to do with it? Well, the government is not exactly following the advice of economists, yet behind their actions lies the problem of the middle-income trap. “For us, (…) the issue of being stuck in middle-income (…) is a central political issue, and it is a background explanation for the social debates”, writes economist Ákos Bod Péter, former president of the Hungarian National Bank, in an article.

Capital, labour, land, enterprise

So how is the issue of the mass resettlement of battery factories and the equally mass influx of migrant workers related to the middle-income trap? We will need one more economic concept in order to grasp this (I promise this will be the last). The concept is called the factor of production. Factors of production are inputs into the production process (inputs) so that out of the production process come goods and services (outputs).

Classical economics recognises three factors of production: capital, labour and land, i.e. natural resources. Modern economics does not argue with this either, but simply adds a fourth factor, entrepreneurship, which is essentially innovation – the ability to combine the factors of production in novel, innovative ways.

What about the factors of production? We have little capital, and capital has always been lured by successive Hungarian governments. Márton Nagy, Minister of Economic Development, recently announced that the government's goal is to double the stock of foreign working capital, or FDI, which currently stands at EUR 100 billion, by 2030.

What about work? We can also talk about the quality and quantity of labour. The government is reluctant to invest in labour quality. Hungary has one of the lowest rates of tertiary education in Europe, with 40 per cent of eighth-graders not even able to understand basic text. In terms of the labour force, employment has grown significantly over the past decade and the government no longer seems to believe that this can be increased.

Work? Dear investor, bring it in yourself!

Just how much the government does not believe is clear from the Aliens Act mentioned above. Although the preamble trumpets that “Hungarian jobs are also first and foremost for Hungarians”, there is no sign in this law or in any other government proposal that a programme is being launched to mobilise the Hungarian labour reserve. There is no sign that, for example, there will be a chance for people from a small village to go out to look for a job, and then begin working.

The Hungarian state does not spend any substantial sums on active labour market instruments; it does not really try to help those who are outside the labour market. And yet the Hungarian employment rate could be improved: many EU countries have a higher employment rate than Hungary. Mobility support, training support, mentoring for jobseekers – these are the kind of things we would read about in the legislation passed last December if the government were serious about Hungarian jobs being for Hungarians first and foremost.

But what can we read in the law instead? For example, that there will be guest workers working on projects whose employer has signed a contract with the Minister of Foreign Economic Affairs or accepted its offer of support for the implementation of the project. There is no maximum number of workers, which means that the minister can issue any number of permits (i.e. “prior group work approval”) for such purposes.

The law provides that preference should be given to the applicant if the workers' accommodation is in an area separate from the local residents (do the government think that this will make the presence of guest workers unnoticeable?). Furthermore, the law provides guest workers working in Hungary with an employment residence permit and a guest worker residence permit. The number of these residence permits is determined by the government on an annual basis (as it was before).

In effect, therefore, it is a matter of allowing any number of guest workers to enter each year, as determined by government decree, and in addition to that, any number of residence permits can be issued to guest workers working on government-subsidised projects. What is more, there are seasonal guest workers.

There is therefore no question of this law jeopardising the government's original idea that the new battery factories that have been hastily built will be run largely by guest workers, as is already the case.

Just how much the government's vision is not threatened is shown by the fact that Pensum, a temporary employment agency that brings migrant workers to Hungary, listed on the Budapest Stock Exchange, issued a press release before the adoption of the Aliens Act, saying that the bill, if passed by parliament, could have a positive impact on their business.

The law passed at the end of last year clearly shows that the government believes we are running out of labour as a factor of production. So, it is saying to the investor, “Bring in the labour from wherever you want – I will provide the legal framework, if I cannot provide the labour.”

Business and natural resources

And what about the enterprise as a factor of production? As we said, here we have to think mainly about innovation, the entrepreneurial spirit of innovation. But for innovation to be widespread, it is important that schools develop children's creativity and critical thinking skills, or at least teach them to read – neither of which the Hungarian school system excels at.

It is also significant that the ability to innovate is more important for entrepreneurial success than government connections, and there is no need to fear that too much entrepreneurial success will result in a takeover bid that is not advisable to reject. So we can hardly build on entrepreneurship as a factor of production.

Which factor of production will then remain? Land; natural resources. What the government wants to and can offer to investors are Hungary's natural resources.

Land that is covered with factory and production waste, on which we can no longer grow food. Our water, which is becoming scarcer because of climate change, and of which our agriculture needs more and more. The lax environmental regulations and the disregard for the authorities that allows investors to pollute our natural environment with their production in a way that they could not do anywhere else.

This is the new recipe of the Orbán government, and this is the new economic model for Hungary today.

This recipe will significantly increase Hungary's GDP. So, at first, it may seem to many that Hungary has escaped the middle-income trap. This will of course be an illusion, but a spectacular one. At the level of macroeconomic numbers, Hungary will – for a while – look like a success. Huge economic value can be generated based on the exploitation of nature.

Marx already pointed out that not labour, but nature itself, is the source of all wealth. But economic success will only be apparent and temporary, because the government will offer our natural treasures to investors for use without having to see to their renewal.

There will be a high price to pay for the illusion of success, not only for future generations, but also for us, as environmental change accelerates.