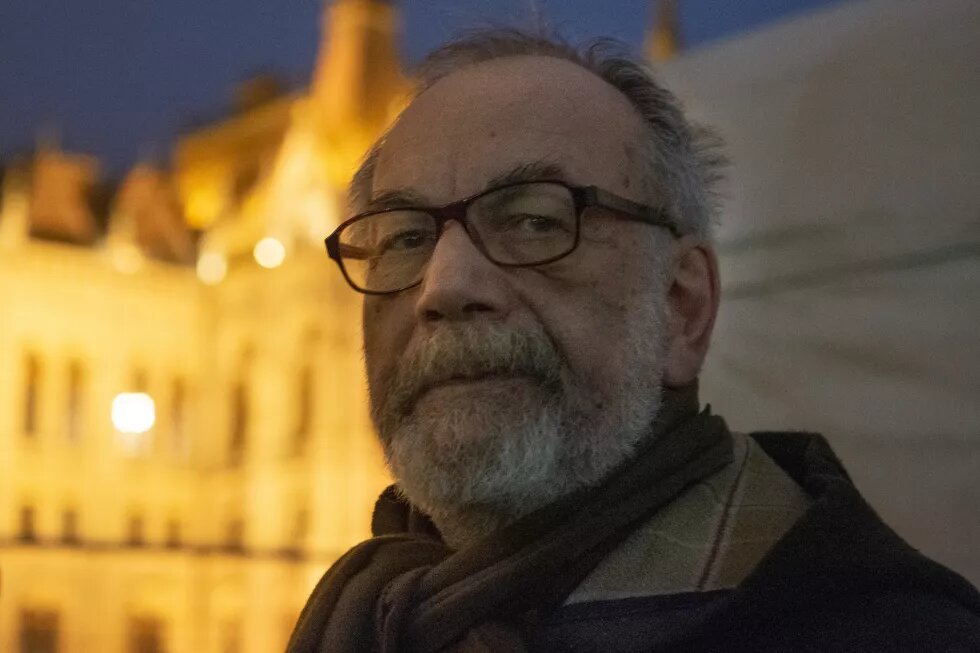

One of the most important contemporary Hungarian thinkers, the once-liberal, later Marxist philosopher who captured Europe’s disorientation after the Cold War by coining the term post-fascism “to describe a cluster of policies, practises, routines and ideologies present in the contemporary world”, the writer and scathing political critic, Gáspár Miklós Tamás, the father of four children, also known as TGM, passed away at the age of 74 on 15 January 2023 in Budapest. He had been dealing with a long-lasting disease with dignity and with the willingness to live an intellectually fruitful life all the way through.

“…in today’s world a condition pertains to which I have given the name, post-fascism. What I mean to invoke by this term is not the claim that the SS is stalking Europe once more! But that all the aims of the right-wing totalitarian machine of the pre-war period, let’s name them of the fascists, can nowadays be achieved and are being achieved by parliamentary and democratic processes,” he wrote in an eerily poignant, prophetic essay published in Open Democracy in 2001, labelling himself an “unillusioned critic of a racialized global liberalism”, accusing Europe and the world of “abandoning Enlightenment principles”.

In the same essay he wrote about himself: “I am myself a half Jewish Hungarian, brought up in Romania by a family full of communists. My parents were in an illegal communist party, and spent a long time in prison for it. Basically they were very disappointed people, who didn’t like the regime very much, from a left-wing standpoint. Consequently, I had what I can call an impeccable anti-communist education at the hands of my communist parents.”

An intellectual rock star

The Romanian-born intellectual emigrated to Hungary in 1978, where he became a pillar of the democratic opposition during the communist Kádár era and member of the first democratically elected Hungarian Parliament between 1990-94. He held the role of a visiting professor at the Central European University (CEU), Yale, and other renowned universities in the USA, the UK and France. Despite his fame, he lived in humble circumstances, due to the fact that he lost his job during the Kadar regime for political reasons and in 2010, following Orbán’s return to government, he was pensioned early by the Philosophical Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, a fact that he considered lawful, but unfair. In Hungary he grew into an “intellectual rock star”, a “brand name whose opinion counted as an orientation system”, as Péter Pető, editor-in-chief of the independent online media outlet 24.hu, put it in the commemorative livestream on the crowdfunded, independent YouTube channel Partizán just a day after TGM’s passing.

Last March, the ELTE Institute of Philosophy and the ELTE Institute for Art Theory and Media Research organised a conference entitled The TGM Effect, which paid tribute to TGM’s work, to the possibilities of Hegelian Marxism, and to his reading of Marx. The eight-hour video, which features the philosopher himself watching the conference via Zoom from his living room surrounded by endless piles of books and antique furniture (he could not attend in person for health reasons) was livestreamed on Facebook and is still available there, while the lectures were published in the literary magazine Élet és Irodalom.

TGM – the prophet and conscience of the Hungarian nation

The introductory lecture by Sándor Radnóti, Professor Emeritus of the Aesthetics Department at ELTE, defined Tamás’ philosophical nature as follows: “I would call him a Romantic, not in his philosophical content, but in his feeling. It should be noted that he often uses criticism of science, mocking the only scientific position that is considered correct, the superiority of experts, but this in no way implies a lack of science, rather a different - and highly reasoned - science. It is, nonetheless, characterised by a passionate subjectivity that in the philosophical tradition was perhaps unique to Rousseau, Fichte and Nietzsche. […]

Tamás is characterised by an extraordinary wealth of thought, the ability to deploy huge amounts of historical material and to keep a wealth of cultural knowledge at his disposal at all times. His notorious U-turns are not indicative of impermanence, as is sometimes accused, but of original, intellectual metamorphoses that are rare in their sharpness, albeit not unprecedented. The young [Hungarian Marxist philosopher] Georg Lukács' 'going all the way' is similar to this, in mutually-exclusive Kantian, Hegelian and mystical directions. Lukács found his final intellectual home in Marxism, as did Miklós Tamás Gáspár decades later - in a different way, because he was not in the party - in the company of the late Moishe Postone, Jacques Rancière, Antonio Negri, Slavoj Žižek, Alain Badiou and others.”

As a tribute to his 70th birthday a few years ago, the leftist online portal Mérce republished some of his most significant works, such as Communism on the Ruins of Socialism or Telling the Truth about Class. His last essay published on 26 December 2022 by Mérce, entitled Five Pieces of Advice to the Homeland, contains among other matters a list of works of art, literature, music, and philosophy the reader should become familiar with as a means for “(…)our fellow citizens who read Plato and Dante and Ady, who listen to Palestrina and Mozart and Bartók, of preventing a quasi-fascist, post-fascist barbarism from becoming a regime again.”

Humour in times of dictatorship, relentless social sensitivity

The sense of humour that accompanied him through the darkest hours of the dictatorship is well highlighted in the following anecdote, recounted by another philosopher with Transylvanian roots, Mihály Szilágyi-Gál, and published in Transtelex, the independent Hungarian voice for Transylvania supported by reader donations. TGM was living in London in 1987 when British intelligence told him that as an oppositional dissident of the Hungarian People’s Republic, he was being watched by them. They had also noticed he was being watched by a system outside of the Brits’, which was not surprising, since he was a Hungarian citizen. What they did not understand, though, was why a third system was watching him too. Tamás responded: “Well, those are the Romanians.” The officer then wondered whether this wouldn’t cost a fortune, given that these were poor countries, after all. Tamás reluctantly answered: “You see, that's the difference between dictatorship and democracy. A dictatorship can spend on the surveillance of an oppositional foreigner even if there is no bread in the shop.” “Oh, thank you”, said the officer, “that was very instructive!”

Besides his sense of humour, he was also characterised by an overcritical nature that would relentlessly correct others, often for what he considered linguistic mistakes, and his watchful eyes were concerned with all sorts of class inequalities. In one of his final interviews with Partizán last October, he described his long-term experience as a patient in the hospital waiting room, where he would encounter the loneliness, vulnerability and abandonment of middle-aged village women. “In many small villages”, he said, “there is no more post office, no library, no coffee shop, no priest.” He spoke about his astonishment concerning the story of a severely ill woman in her fifties who rode the 5 am factory worker bus, the only one that would take her from her village to Budapest and then, arriving way too early at the Oncology Institute, where the hospital doors were still closed for outpatients at 6:15 am, so she would wait for hours in a random doorway.

Positive Hungarian and international reception

Both opposition and government-friendly media outlets have reacted to his death with emotional, respectful obituaries, a rare phenomenon in a country notorious for its deep political rifts. Even Viktor Orbán, whom he had often severely reprimanded for his antidemocratic politics, expressed his respect in a Facebook post that read “Gone is the old freedom fighter. God be with you, TGM!” His life and work were also remembered worldwide, from Germany to France to Canada.

As per his will, his son first broke the news of Tamás’s passing to Transtelex, the birth of which TGM was thrilled to welcome in February 2022 as a ray of hope for much-needed media pluralism. Back then he wrote: “Hungary also needs another perspective, especially in the current phase of pathological degeneration. Let's see if free, original voices can be heard from Romania, Serbia and Slovakia, which […] can save Hungarian minds from ignorant clichés and mechanical emotions. Maybe someone will finally help.”

Almost a year later, Transtelex published Ábel Tamás’s words: “My father died. He fell asleep peacefully. In the same hospital room, on the bed where […] almost a year ago […] he typed on his phone the article on the birth of Transtelex. He loved everything (and everyone) that was (and is) brave, rebellious and fighting for freedom. Thus he loved Transtelex and its editors, especially as he constantly longed to return home to his native Cluj.”

Proofreading by Gwendolyn Albert.

Also published by Heinrich Boell Stiftung about TGM: