In 2018, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán stated that he wanted to establish a new social contract with Hungarian women about the future of Hungary and their role in it, because the demographic future of the country hinges on them. Having children is the most personal public matter – as Orbán put it – and therefore it is essential to listen to the needs of women and offer them predictable prospects.[1] What exactly are these prospects that the Hungarian Government has been offering, and what are their outcomes? This article summarises Hungarian pronatalist policies, the narratives around them, and their social consequences.

Pronatalism can be understood as both an ideology and as a governmental aspiration to increase fertility in a nation. Pronatalist family policies create financial incentives and social infrastructures in order to raise birth numbers. Pronatalism can also be understood as a cultural and normative narrative, in which having children is the natural duty of women and being a mother is a central part of women’s identity. Its underlying ideology suggests that motherhood is a patriotic obligation, and the policies that stem from it aim to control the dynamics of fertility, its rationales and its consequences.[2] Pronatalism is often related to right-wing politics, especially in connection with patriotism, although there are examples of pronatalist politics pursued by left-wing governments as well. For example, in Hungary during the state-socialist era there was an infamous ban on abortions between 1953 and 1956, and people born at that time were called the Ratkó-children (the name of the Health Minister during that era). The Orbán administration, returning to power in 2010, questioned the superiority of Western democratic models and envisioned a bright national future while criticising the EU and the UN for their migration policies.[3] They have defined domestic population growth as a desirable alternative to immigration. Population growth has been connected to traditional gender roles, and what Orbán calls ‘gender ideology’ soon became Public Enemy No. 1. Yet fertility was not deemed as desirable across all social groups, so the Government has realised selective pronatalism,[4] where mostly the (upper)-middle classes were encouraged to bear children. However, the communication strategies and the policies that came to be implemented seemed to diverge at times. The following section takes a closer look at several of the policies introduced during this era.

‘GYED extra’

The only persons eligible for the state benefit for childcare (GYED in Hungarian) are fathers or mothers who were formally employed prior to the birth of the child, and the total amount provided is a certain percentage of their wage. In 2014, supposedly due to labour shortages, the Government introduced ‘GYED extra’, which means a parent can return to the labour market after the child’s first birthday without becoming ineligible for full childcare benefits. In 2016, return to work after the child was just six months old without losing eligibility for childcare benefits became possible. This creates better opportunities for women, as they are able to receive the benefit and a wage at the same time, encouraging them to return to the labour market.

Family tax system

The Government also introduced a new family tax system in 2010, with the aim of achieving a demographic upswing. Parents with one or more children are eligible for tax relief, which increases with the number of children. A certain amount is extracted from the personal income tax and added to the net salary, thus reducing the difference between gross and net salary. While the amounts are fixed, a parent might not earn enough to be able to claim the total tax relief if the amount of their income tax is too low, thus this policy also prioritizes big families with high income. . People outside the formal labour market are excluded from it, and therefore this policy hardens the division between social classes. Moreover, it has been criticised for being neoliberal, because the benefit is in the form of tax relief instead of direct financial transfers.[5]

‘CSOK’ (Family housing benefit)

The new family housing benefit has become one of the Government’s flagship policies since its inception in 2015. Families can apply for 10 million forints, an equivalent to EUR 24000, in grants (which do not have to be repaid) and another 15 million forints in subsidised loans which can be spent on buying or building a new house or flat (this was extended in 2019 to second-hand properties as well) if they agree to have children or already have children (the amounts increase from one to four children). There are several conditions for this benefit, such as previous employment and marriage (except if a couple already has children). However, the grant must be paid back if the family does not live in the house for a defined period of time or if they eventually do not have as many children as promised. This raises concerns, as last year 18,000 couples got divorced, even though divorce rates have been declining in the last few years.[6] Moreover, if people take out such a loan and are unable to pay it back to get out of the obligation, they may still feel forced to conceive children to meet the terms of the loan even if they have changed their minds about being a couple.

Baby loans

The Government announced a seven-point family protection action plan in 2019. One point was the “baby loan” for young, married couples. The more children they have, the less money they have to pay back, and after three children the loan is forgiven. The conditions also include employment and marriage. It also favours those who have a steady financial background and thus are able to take the risk of paying the loan back in case they fail to conceive.

Personal income tax exemption for women

This tax exemption is also part of the above-mentioned action plan. Women with at least four children are exempt from personal income tax for the rest of their lives. This policy encourages women to take on roles both as a parent and in their careers, but as a form of support, it is just provided to women in the formal labour market, thus putatively promoting a ‘work-based society’. However it does not change the wage gap between women and men, which is still an issue in Hungary, as there has been the fifth biggest wage gap in 2020 amongst EU countries[7].

Car purchase program for large families

As another part of the action plan, families with at least three children receive a benefit that can be spent on the purchase of a new car with at least seven seats. This policy targets just (upper) middle-class families, as the benefit covers merely a small fraction of the price of a new car.

Day nursery

Since 2018, all municipalities must have a day nursery if there are more than 40 children under the age of three resident there, or if at least five families demand one.

Modification of the abortion-law

The most recent pronatalist policy was introduced in September this year. Although in 2012 the Fidesz-Government already included in the Constitution that the life of the fetus is entitled to protection from the moment of conception, which has led to assumptions that they are inclined to change abortion-laws, it has not happened until 2022. The Minister of Interior issued a decree in September, declaring that pregnant women who want an abortion are obliged to be presented with “the factor indicating the functioning of fetal vital functions”, meaning the heart sound of the fetus. The decree has not been preceded by social negotiations and has led to great outrage, which is not surprising, considering that 70% of Hungarians support legal abortion[8]. Although the law modification does not pose a legal obstacle to abortions, it can be traumatising for women already in vulnerable situations and reflects the opinion of the Government about women: unable to make responsible choices and thus in need of guidance. This policy might not have a huge effect on the demography of Hungary, but it means a great shift in the politics of pronatalism from the positive pressure of benefits to the negative pressure of guiltiness.

Several of the aforementioned policies target those in formal employment, while the benefits aimed at the wider population have stayed at the same nominal level (and taking inflation into consideration, their value has been declining). This strategy can be called selective pronatalism, where the government chooses to incentivize certain social groups to have children, in this case the working middle class. This is clear from the communication of the Prime Minister, whose vision is a work-based society, as he said when he first laid out the concept in 2014. An analysis[9] of Orbán’s family policies concluded that their ideology is inconsistent regarding gender, as single parents and even non-heterosexuals can benefit from some of them (e. g. tax benefits, day nurseries). Moreover, many of the policies support women’s participation in the labour market, not just their traditional roles. By contrast, when it comes to the social classes that the policies target, there is a notable degree of consistency with the (upper)-middle classes as the key beneficiaries. The analysis also highlights that although Hungarians tend to have a conservative, family-oriented attitude, according to polls they no longer follow the traditional family model in their own lives (e.g. divorce or extra-marital affairs are no less common here than in the rest of the European Union)

In addition to the substance of these policies, the discursive communication of the Fidesz administrations since 2010 has placed family values at the centre. As they have enshrined in the Constitution, a “family” consists of a mother, a father, and their children; therefore childless couples, single parents and non-heterosexual people have been excluded from the ideal and legal definition of a family. The reason for this is simple, according to the Government’s narrative: the survival of the Hungarian nation is at stake, and it is the responsibility of women to counteract this decline. This idea has been vocalized by several politicians, for instance by the Prime Minister himself when he stated the need for a new social contract with Hungarian women, thereby disregarding the responsibilities of men. Most emblematically, when asked to define the Hungarian nation, he said that “You are Hungarian if your grandchildren are Hungarian too.”[10]

Other politicians from the governing party often employed pronatalist narratives as well. The former speaker of the National Assembly, László Kövér, once stated that those who do not want children are on the road to self-destruction and that the world will be ruled by those who populate it with children.[11] He also expressed his hope that “our daughters would find the greatest fulfilment in giving birth to our grandchildren.”[12] During a debate on domestic violence, another politician from the governing party stated that if only women would give birth to several children there would be no domestic violence and that they should “go and emancipate themselves” only after that.[13] The (then) Family Affairs Minister, Katalin Novák, who since May 2022 is the Hungarian President, published a video in 2020 where she said women should not give up on their “privileges” (by which she meant the conception and delivery of children) as part of a misunderstood emancipatory fight.[14] This video got a lot of criticism for not acknowledging the disadvantaged situation of women and especially working mothers, or her own privileged situation. There is, therefore, a consistent ideology behind the communication of the ruling party, which aims at strengthening traditional gender roles.

The impact of Hungarian family policies

The Hungarian Government has emphasized the importance of having children and allocated an outstanding share of the public budget to family policies since 2010. For instance, spending on family benefits has reached 4.6% of Hungarian GDP, and thus the country has become the fourth-highest spender in terms of the share of family benefits in all social spending among European countries.[15]

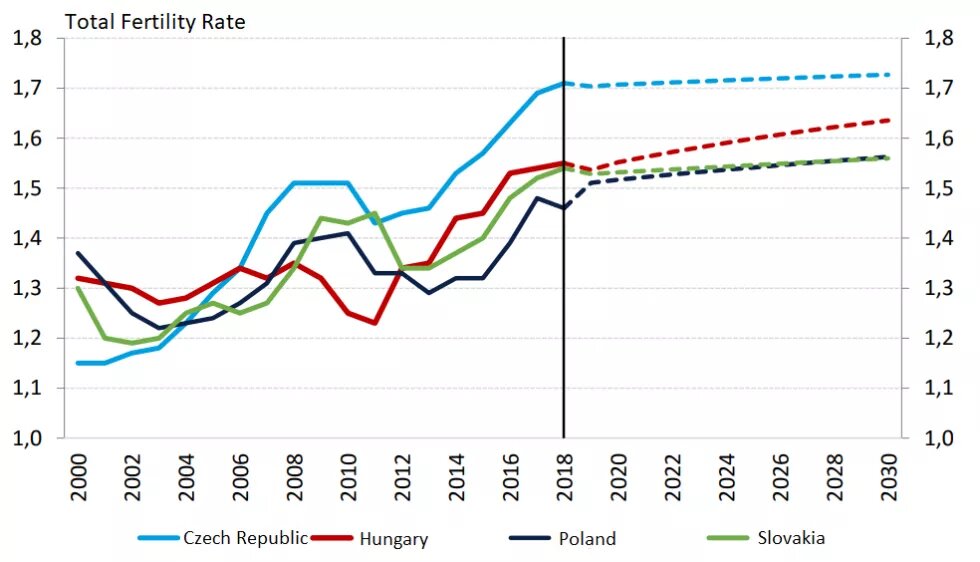

The aim of the Government is to reach the value of 2.1 in the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) by 2030, which is generally deemed the required level for the reproduction of the population (excluding net migration). The TFR of Hungary has been increasing since 2010, but this is also true for the other Visegrad countries (Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia), as can be seen in Figure 1 (real data until 2018, projections thereafter). According to the Central Statistical Office of Hungary, the Hungarian TFR in 2021 was 1.59.[16] Sceptics argue, however, that just a small part of that increase is due to family policies, as the overall trends are largely driven by economic upswings and downturns.

Although the overall impact of family policies is limited, certain elements of them do have a significant effect, according to a study that examined the impact of the family benefit system between 2010 and 2014.[17] Among the determinants of fertility rates, the study highlighted factors related to reemployment after childbearing, increases in disposable income, and better housing prospects. The policies introduced after 2014 mostly fall into these areas, such as the family tax system, family housing benefit, the baby loan and the tax exemption for women having four or more children, while the car purchase benefit and the development of day nurseries fall outside of these categories. In a nutshell, Hungarian family policies have a slightly positive, significant effect on fertility.

Conclusion

The Orbán administration has been pushing through its family policies in a great rush to achieve a demographic upswing. While their communication and symbolic politics reflect the traditional division of labour between genders, where the responsibility for childcare is squarely put on women, their actual policies are less black and white. Most of their measures favour people in the formal labour market, especially the (upper)-middle classes. These policies mostly include loans and tax breaks, while universal benefits are losing their value, thus dividing society between those whose childbearing is deemed worth supporting and those whose childbearing is deemed not worth supporting. However, several of their policies encourage women to return to their jobs after childbearing, and some are even helpful for lower class people as well, such as the development of day nurseries. The Government’s communications and its policies are therefore distinct from each other, which perfectly echoes the divergence between how Hungarian society views traditional values and how they actually live their everyday lives in practice.

[1] https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/hu/a-miniszterelnok/beszedek-publikaciok-interjuk/orban-viktor-a-kossuth-radio-180-perc-cimu-musoraban20180420

[7] https://www.penzcentrum.hu/karrier/20220308/nesze-neked-nonap-europai-szinten-is-durvan-kevesebbet-keresnek-a-magyar-nok-mint-a-ferfiak-1122798#

[8] https://www.penzcentrum.hu/egeszseg/20220916/itt-all-feketen-feheren-egyre-kevesebb-az-abortusz-megsem-szuletik-tobb-gyermek-magyarorszagon-1128982#

[12] https://www.origo.hu/itthon/20151215-kover-laszlo-fontos-kozbeszed-resze-legyen-demografia.html