THE POLITICAL MAP OF SLOVAKIA IN 2020

Slovak political landscape is exceptionally fragmented ahead of February 29 general elections. One of the last opinion polls published before the election polls moratorium foresees eight parties to be represented in the parliament. However, conceivable scenarios include 6 to 12 parties possibly entering the parliament. This pre-election analysis was published by EuroPolicy in cooperation with the Prague office of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

February election are taking place against the backdrop of the profound development Slovak society and politics has undergone since the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová in 2018. Although the believed perpetrators are currently on trial, new revelations on the high-level corruption and state institutions paralyzed by toxic connections are still being intensively covered by the media.

Despite enormous scandals and dwindling support, the social conservative SMER-SD (member of PES), the party that has dominated the Slovak politics for the better part of the most recent 14 years will most likely be the nominal winner of the elections. The party still scores 17% support. Major worrying feature of the upcoming elections is the increasing potential of the extreme-right party Kotlebovci-ĽSNS (no affiliation), now in opposition and currently the third most popular party in Slovakia (10%).

Besides ĽSNS, the opposition spectrum counts six parties with realistic chances of getting to the parliament: an eclectic movement of personalities without standard party structures, OĽaNO (ECR), which has surprisingly climbed to be the most popular among them with 15 %; two new parties: centre-left coalition Progresívne Slovensko/Spolu (Renew/EPP) and centre-right Za ľudí (no affiliation so far), the party founded by the former president Andrej Kiska; a party led by a celebrity businessman Boris Kollár called Sme Rodina (ID

Party); economic liberals SaS (ECR) and the Christian democrats KDH (EPP), the longest-standing party in modern Slovak history that has a shot at returning to the parliament after four years.

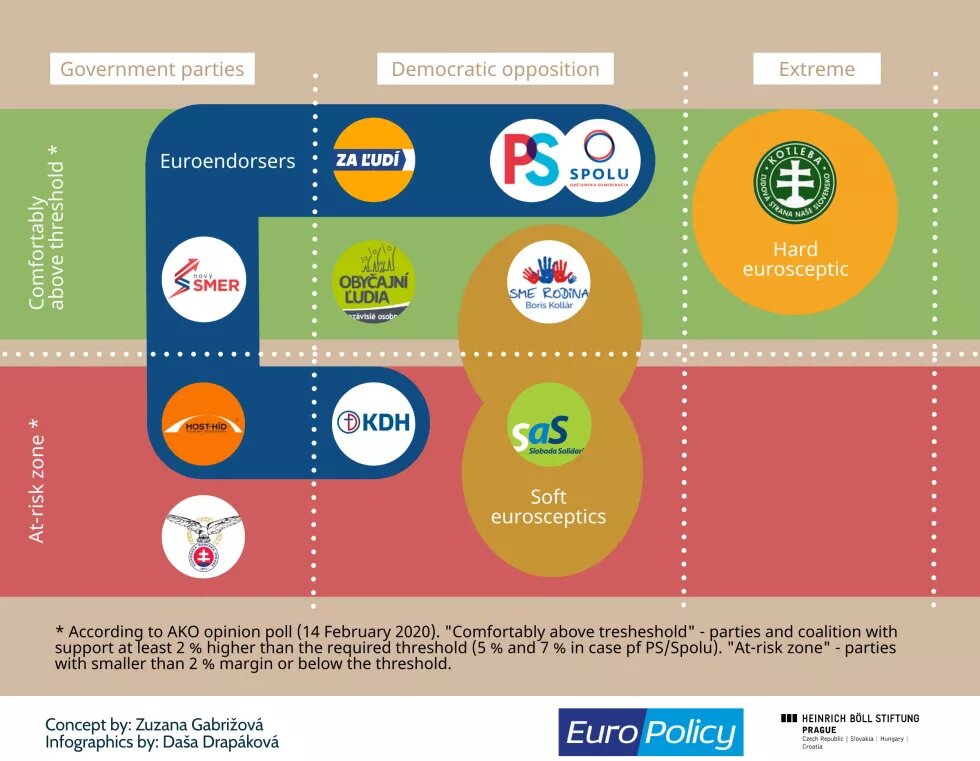

With this level of fragmentation, any predictions are problematic. Much will depend on which of the parties, whose support oscillates around 5 % will eventually end up in the parliament (see Figure below). This would change the post-electoral scenarios dramatically. Both current junior coalition partners: nationalistic SNS (no current European party affiliation) and Slovak-Hungarian party Most-Híd (EPP) are in the risk zone as their support has plummeted in the past months.

There is a plausible scenario in which the opposition parties (with the notable exception of the neofascist ĽSNS) form a government, one that would be comprised of five to six parties and thus possibly quite fragile. Alternatively, SMER-SD might be able to form a government with the silent support of ĽSNS, although prime minister Peter Pellegrini (SMER-SD) has openly rejected this option. Other development alternatives are cannot be entirely excluded, especially given the uncertainty in terms of who gets in the parliament, but most opposition parties reject the coalition with the ruling SMER-SD.

SLOVAKIA IN THE EU

Topical study of Comenius University analysed the Euroscepticism of Slovak political parties ahead of elections. Using data from TV debates and Facebook posts as well as data from the election manifestos, authors placed the parties on the scale of academic definition of Euroscepticism. According to their findings, only ĽSNS can be considered as a hard-line Eurosceptic party, while two opposition parties – Sme Rodina and SaS – have a tendency towards soft Euroscepticism. SMER-SD, Most-Híd, KDH, Za ľudí, and PS/Spolu are all parties supporting further EU integration, but none goes as far as to be described as Eurofederalist. Two parties, SNS and OĽaNO, could not be decisively placed in neither of these categories, given their conflicting messaging towards the EU.

European issues are largely missing among the general campaign narratives and are debated only in certain well-informed, insider circles (experts, diplomats, expat community). EuroPolicy/EURACTIV.sk has analysed and compared positions of the relevant political parties (SMER-SD, OĽaNO, PS/Spolu, Za ľudí, Sme Rodina, SaS, KDH, SNS) on the most pressing European agenda. The resulting study covers specific questions put to the parties across ten areas: Slovakia´s internal handling of the EU agenda, energy and climate policies, Eurozone governance, agricultural policy, regional development with the use of EU funds, digitalisation, justice and home affairs, gender issues, foreign affairs and security policy. Two main sources were used: parties’ manifestos (in some cases, manifestos are missing: SMER-SD, ĽSNS) and interviews with party experts on the particular area. ĽSNS is not taken into account by the analysis at all, as the party has not provided us with any answers.

Following chapters provide an overview of a few selected areas. Firstly, the analysis looked at proposals on how to improve Slovakia’s performance in the EU. One of them is to move the coordination of the European agenda from the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs to the Government Office of the Slovak Republic. Parties calling for this measure (PS/Spolu, Za ľudí, partly SMER-SD), supported by a part of the expert community, argue that the ownership of the EU sectoral policies at some ministries is unsatisfactory, which is why the EU affairs must become the prime minister’s agenda. This notion was met with a stark rejection by the outgoing foreign minister of 10 years, Miroslav Lajčák (SMER-SD), who advised against it in a recent speech before the diplomatic and expert community.

Moving from procedural framework to substance, what are and what should be Slovakia´s priorities in the EU according to the political parties? Naturally, the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-2027) is high on almost everybody´s agenda. European funds still constitute a huge portion of public investments in Slovakia. European Green Deal also takes a central stage as political parties slowly embrace the inevitability of climate-friendly policies and accompanying transition funds allocations. Specific to Slovakia is the concern for the automotive industry, one of the pillars of the economy, and its adaptability to a carbon neutral future.

The Visegrad cooperation is relatively prominently mentioned in manifestos of Slovak political parties. Traditionally, the V4 group is the main go-to reservoir of allies in the EU. Opposition parties maintain that Slovakia´s coalition building must go further. While no party questions the existence of the V4 or the need to maintain constructive neighbourly relations, some call for more distancing from the policies of Hungarian or Polish governments. Za ľudí party goes as far as saying that Viktor Orbán has usurped the V4 brand, communicating Hungarian positions under its umbrella without consulting other partners.

RULE OF LAW, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS

As a V4 member, Slovakia has not been very vocal so far in the European rule-of-law debate. Whether in the case of Poland or Hungary case, Slovak government has always been a believer in dialogue before sanctions (article 7 procedures). There is little appetite among political parties to considerably strengthen the EU´s toolbox in overseeing the democracy and rule of law in the member states. The only exception is the PS/Spolu coalition (PS´s MEP Michal Šimečka from Renew group has become European Parliament´s rapporteur for the new rule-of-law mechanisms). The party claims to support not only a peer-review among member states but also annual monitoring including sanctions and EU funds conditionality. Linking EU financing with rule of law is a red line for most of the other parties, but some would not protest against EU annual assessments in the rule of law (OĽaNO). Za ľudí deems unacceptable that “EU institutions put up more fight for the rule of law than the countries concerned” but does not go as far as to support more leverage on the EU’s side. Sme Rodina and SNS have similar position. SaS believes that EU institutions lack proper understanding of the Slovak reality. KDH representatives don’t have a unified position on the matter. SMER-SD’s opinion is unknown.

European Public Prosecutor´s Office, on the other hand, has an almost unanimous support. Some parties are cautions as to how the new institution will fit in the national systems once becoming operational. Several parties would be willing to hand the new body more competencies, such as international crime, corruption, terrorism (PS/Spolu, SaS, KDH). SNS warns against possible “meddling” into national competences. OĽaNO would prefer seeing more countries join the enhanced cooperation before new competences are added. Za ľudí highlights the need to strengthen national capacities in this area.

There is a unanimous agreement among Slovak political parties on refusing mandatory refugee quotas and keeping the asylum decisions in national hands. A few parties show willingness to provide more help to the countries most affected by migration, some (KDH, PS/Spolu) implicitly saying Slovakia has the capacity to host at least some people should there come to it. Other than that, no party has a clearly elaborated position on how the European asylum system, or the Dublin IV regulation should look like. PS/Spolu calls for a “just and effective” reform, Za ľudí supports more funds allocated from the EU budget to the countries under migratory pressure. SaS favours the disembarkation platforms, or any other solution that would place processing of the asylum requests outside the EU territory.

GENDER ISSUES

Over the past few years, gender issues have become a rather surprising bone of contention of Slovak politics. The lines of conflict divide the conservative and more liberal part of the society and political spectrum. “Gender agenda”, understood as an ideology is being portraited as evil by the Church and more conservative strains of politics. Topics such as fight against gender-based violence (COE’s Istanbul convention) or dismantling of gender stereotypes unsettle politicians of a more conservative nature.

It therefore comes as no surprise, that most of the Slovak political parties do not reflect specific situation of women in the society. The only women-supporting measures are those linked to maternity, that is, support for women on maternity leave, in some cases single mothers (parents) and family-friendly policies in general (KDH, OĽaNO, SNS). Only two parties tackle the issue of gender pay gap (PS/Spolu, Za ľudí), a part of the European pillar of social rights. Also, European Commission will present proposal on pay transparency.

PS/Spolu and Za ľudí want to tackle the gender pay gap also at the national level, by making the average wage of men and women sorted by positions in larger companies and public institutions. PS/Spolu also calls for anti-discriminatory measures in the labour market and “temporary equalizing measures” in professions where women are scarce. Other parties either do not see this as a priority (SaS, KDH, SMER-SD), or do not see gender discrimination as part of the gender pay gap problem. OĽaNO claims women with children are paid less because they are perceived as less reliable employees.

Forthcoming EU’s Gender Equality Strategy will also address gender-based violence. Linked to that is the possible ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (the Istanbul Convention) by the EU. Only two parties (PS/Spolu and SaS) would support ratifying the Istanbul Convention, both at national and European level. Za ľudí would agree only to national ratification with a stipulation meaning that Slovakia would not implement some provisions, to “disperse concerns”.

Should the ratification of the Istanbul Convention prove unattainable in the EU, the European Commission mulls to propose adding violence against women to the list of EU crimes. Again, only PS/Spolu would support such a proposal. OĽaNO and KDH reason that firstly a definition of gender-based violence must be found. KDH disputes the mere term “gender-based violence”. More specifically, they oppose the term “gender” as a “social construct independent from biological sex”.

ENERGY AND CLIMATE

The main objective of the EU Green Deal, introduced by the European Commission in December 2019, is to reach climate neutrality by 2050. This objective is currently supported by all EU Member States with the exception of Poland. Slovakia signed up to the objective last year through its highest representatives, President Zuzana Čaputová and Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini.

This view is now shared by most Slovak political parties. Only SNS and SaS break the ranks: the view of the former is unknown, and the attitude of the latter is unclear. However, both political forces share the opinion that greenhouse gas emissions need to be reduced.

These differences do not translate directly to the views on carbon border adjustment. The measure is suggested by EU Green Deal in case other big economies do not sign up to significant emission reductions. Its aim would be twofold and relevant for Slovakia: export EU’s climate ambition and create a level-playing field for the industry.

In Slovakia, carbon border adjustment is supported by SaS, Sme Rodina, OĽaNO, PS/Spolu, KDH and SMER-SD. Za ľudí doesn’t have a clear opinion and the view of SNS is unknown.

As for renewables, another issue treated by the EU Green Deal, Slovakia has committed to reach a 14-percent share in the final energy consumption by 2020 and 19 percent by 2030. The latter goal still has to be agreed by the European Commission. However, the country has trouble reaching the 2020 goal, its share stagnating in the recent years (12 percent in 2018). All Slovak parties support the development of renewables in Slovakia, emphasizing especially the potential of solar energy and local renewables. Several parties suggest the development of wind energy, biogas and geothermal sources. At the same time, they see the need for public acceptability, and limited impact on energy prices and on the environment.

On the path to reach climate neutrality, Slovakia counts on a high share of nuclear energy. Two new reactors are under construction at the Mochovce power plant, although they are running over time (launch currently estimated in late 2020 and 2021 respectively) and exceed the estimated costs (5.67 billion euro). All Slovak parties agree on the need to finish the two reactors. At the same time, all except SNS criticize the postponement and cost hikes.

The parties are, however, divided by the question of a new nuclear powerplant. SNS seems to support such a project, Sme Rodina proposes new technology and SMER-SD shows at least a conditional support. On the other side, SaS, Za ľudí, OĽaNO and PS/Spolu are highly critical of a nuclear newbuild. KDH doesn’t have a clear opinion.

FOREIGN POLICY

Political consensus on the strategic orientation of Slovakia’s foreign policy (NATO, EU) has been taken for granted for quite some time. First cracks appeared in 2014 after the Russian annexation of Crimea. These cracks have opened wider during the term of the outgoing government (SMER-SD, SNS, Most-Híd). Open pro-Russian narratives questioning the EU’s sanction policy following the Crimea annexation(SNS, SMER-SD), government’s reluctant support to British partners after the Skripal´s case, numerous meetings with representative from EU´s sanctions list by the Speaker of the National Council (supreme constitutional official), or mixed messages towards Chinese representatives, are just a few examples.

Looking at the election manifestos, all of the parties, proclaim pro-European and pro-Atlantic orientation of Slovakia. (One exception is ĽSNS which is challenging both, NATO and to a lesser extent the country’s EU membership). Compared to the past, more caution appears regarding future cooperation with the United States. Foreign policy consensus is still present in less burning issues, such as support for Western Balkan´s European ambitions, neighbouring Ukraine´s development and a strongly accented multilateralism.

One of the most divisive questions related to European foreign policy is the proposal to introduce the qualified majority voting (QMV) to certain decisions within CFSP in the EU Council. This should, proponents argue, make the EU a swifter and more effective global player. Most Slovak parties are wary in this area. While PS/Spolu agrees this should be done for the sake of efficiency, the rest of the political spectrum is much more cautious. For Za ľudí the issue poses a “dilemma”. According to the party, greater European flexibility would, in a long run, “suit” Slovakia, therefore “we will need to switch to it at some point”. SMER-SD prefers a compromise that would “respect the sovereignty aspect, as well as sensitivity of due decisions”. This can be done through a safeguard possibility to request unanimity in the European Council. Similarly, OĽaNO’s position is ambiguous. KDH, SaS, Sme Rodina and SNS are resolutely against this idea.

The current course of the EU´s enlargement is supported by the majority of Slovak political parties. SaS is the only sceptical exception. In their program, the party insists it is better not to accept one new member than to lose another one. Therefore, the party calls for the suspension of accession processes until “the situation within the EU itself is consolidated”. Accession of Turkey to the EU is wholly rejected by KDH, OĽaNO, SNS, and Sme Rodina.

The European perspective for Ukraine, which is - according to representatives of all monitored parties - an imperative component of Slovakia’s development, is explicitly mentioned only in the manifestos of Sme Rodina, OĽaNO, PS/Spolu and KDH. Only OĽaNO has also included the support of Ukrainian membership in NATO. SNS, driven by pro-Russian narrative, opposes these notions.

Despite differences of opinions on dealing with Russia, no party rejects further dialogue with Moscow. The differences are evident when it comes to EU’s sanctions imposed on Russia after the annexation of Crimea – and in the (lack of) willingness to label Russia as a security threat to Slovakia. Although many party representatives, particularly from SNS and Sme Rodina, argue that European sanctions have not yet yielded the desired results, most parties surveyed would be in favour of extending them until the Kremlin changes its policy towards Ukraine (Za ľudí, OĽaNO, PS/Spolu and KDH).

Another major power that has recently become the focus of the foreign policy discourse in Central Europe is China. Unlike its Visegrad partners, Slovakia does not yet have a strategy on how to deal with Chinese investments, neither on how to face the challenge of 5G infrastructure building. “The Chinese challenge” has not attracted attention of most parties. Only PS/Spolu elaborates in this respect, indicating plans to audit existing bilateral trade and investment relations and to reconsider participation in the 17+1 format or the One Belt One Road initiative. Za ľudí refers to Beijing's discriminatory practices towards foreign investors and companies when entering the Chinese market and intends to speak up against them. OĽaNO and KDH stress the need to thematise human rights when talking to Beijing. In particular, KDH would be the most open to side with the USA and to seriously consider the US President's proposal of rejecting Chinese technology in the future telecommunications and mobile infrastructure. Sme Rodina and SNS emphasize economic perspectives in Slovak-Chinese cooperation and propose “sensitivity” and “very careful diplomacy” on human rights issues.